Horsham people’s recollections of the Second World War

and live on Freeview channel 276

The individual can often be forgotten in the grand narratives but these memories, collected from the 1970s to the early 21st century, give people a voice.

The Day War Broke Out

Ron Taylor, choir boy, said: “That particular Sunday I was at the 11 o’clock service and because of the imminence of some sort of conflict, the TA and all sorts of people were at the service. It was announced by Canon Lee that war had been declared and all those in uniform were marched out, then we were sent home, the whole congregation was told to file out.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCliff White said: “One memory … going to Woolworths and having an identity disc engraved and having to wear it on my wrist … from an old drawer a scratched silver bracelet, with the very faint inscription.”

Nina Miles said: “Anyway, I was very frightened because Goering said he was going to have his tea on June 26 in the café in the garden at Weymouth. He didn’t get there, of course, but it was quite daunting.”

Evacuation and Evacuees

The West Sussex County Times of September 1, 1939, carried the headline ‘Horsham is ready for national emergency’. On that day, four train loads of evacuees from London arrived at Horsham station, where buses took them to village distribution centres, with 3,000 billeted in Horsham.

Nina Miles said: “They didn’t want an evacuee. She had told me the day I got there. Well, they were told if they didn’t have an evacuee they would have to have a soldier and she didn’t want a soldier’s big boots on her carpet so they had me ... and of course I may have said I had passed my 11-plus and her daughter hadn’t, which they resented and they got over the situation by sending me for walks all the time. They sent me to the British Restaurant because they couldn’t bear me home at lunchtime but of course I came from a far more cultured home, they didn’t have a book.”

Refugees

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Museum has copies of 40 letters written by Ernest Dieter Ball, a German Jewish refugee who lived at Horsham from 1939 to 1941. The following are just a few of his comments.

September 4, 1939: “I am writing to you from the evacuation. The atmosphere against the Germans is very strong and it is best not to say a word of German on the street because of the reactions are unpleasant, even when you are refugees.”

November 1, 1939: “The school is still very easy for me. I do not think we are going to have examinations because we only get half the lessons we should have. We are not having any music lessons, French or English literature. The worst is woodwork, but from now on I am not going to have it any more.”

September 1940: “Last Sunday, I was a casualty in an air raid practice and I had a wound in my upper leg, it was all very realistic, as a woman who pretended to be hysterical was my mother and she kept on crying like an ordinary person would have done. Then they put me on a stretcher and then in an ambulance and so off we went to the Military Hospital. (Probably the Base Hospital, Roffey). There, we were put in beds and the doctors let the nurses practice on us.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJanuary 16, 1940: Ernest recounts that in a fancy dress competition run by his school, one boy won second prize as Joe Stalin. “A boy from Vienna got the third prize and fourth prize was a Spanish gypsy girl which was me.”

School at War

Ken Parfitt said: “In schools they had great big sheets of pictures of booby trap bombs. There was one I can always remember called a butterfly bomb. I can always remember in Broadbridge School the sheet on the wall showing all do not touch these and there were pictures of little things like that you know.”

Mr and Mrs R. Taylor: “Then at school, when evacuees were absorbed into the school, they tended to get blamed for everything. If things went wrong, they blamed the evacuees because they were different and they spoke differently. There were always jokes about them. They used to say that if they found a milk bottle or two they had found a cow’s nest! All sorts of silly things like that, rather cruel really.”

Hostility to Germans

Ken Parfitt from Broadbridge said: “I can remember there was a family in the village. He had married a German lady before the war. Now I know that people in the village didn’t know whether to speak to her and the awful thing to me now is my mother said ‘oh I spoke to that Mrs so and so she’s really quite a nice person’. Now when you think back, that sounds awful, but there was so much suspicion as I can understand.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA Rotary speaker on ‘task to be faced when victory is won’, from the West Sussex County Times of September 5, 1941: “German children must be given chance to be pure and clean.”

Prisoners of War

John Christian, from Brookfield Farm, said: “We had Italian prisoners of war in the village [Mannings Heath]. They were very good at weaving baskets, getting five shillings a basket, and they also tapped all the birch trees for some kind of ‘hooch’. We employed one of them, they were quite docile. They left, and then we had the German prisoners. They had a tremendous following among the girls. Then we had some Polish lads, they were very sad, they were going to be sent home, many did not want to go. One man dressed himself in his best uniform and carefully hung himself rather than be sent back.”

Bombing and the Air War

Ken Parfitt, who worked for the fire service, said: “Our first call to Portsmouth meant we were there for three days and nights with no food or drink provided. After this experience, our crews carried our own supplies. Later, the Canadians gave us a mobile kitchen, they paid us £3 a week, no overtime. If you were out on a job, you stayed until it was complete. We did three duties on a row.”

Fred Mills said: “If you went to see people of those years, it was quite common to walk around in people’s houses and see a nail in the ceiling with a model aeroplane hanging on a string and well, not everybody, but lots of people had these.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlan McMillan, talking about an incendiary bomb, said: “We had about four on this particular night and I always remember my mum down on her hands and knees watching the garden burning down ... trying to, sobbing away, throwing earth over it trying to put the damn thing out. But we had two or three others that did partly set fire to part of the house but the warden came in and put it out. And then it was funny because the all clear went and we went back to bed and I thought, that’s funny, I can see stars up in the sky. We could see this hole in the ceiling, and a hole in the floor. And we went downstairs, this nice polished oak table, it had a neat half a circle out of the edge of it … this thing had rolled underneath the settee.”

Mr and Mrs Laker, who had an outfitters shop in West Street, Horsham, said blackout cloth was in high demand. They recalled they would drive up to London in the evening to buy it, often in difficult circumstances. Queues would form and many of the local girls often used the cloth for other purposes. The price was 3/11d a yard.

Stan Parsons said: “One day, Walter Jarrett came into the shop and said ‘there’s a Messerschmitt down at Plummers Plain’. So we got in the car and went and cut a lump off the wing, quite illegal! Walt and me, we get the wing out of the back and into the yard and we still had the metal cutters with us so we cut it up into little strips and sold it at sixpence a time for my Spitfire Fund, including the bits with the crosses on!”

A pet’s experience: “We had an old dog, Pat, mongrel dog and he’d disappear during the day. If you were outside and the air raid siren went, you’d see this little figure in the distance and he would come hurtling up the path and if you had the door open he’d go straight up through the house out the back and straight down the shelter. He was the first one in!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlan McMillan, talking about doodlebugs, said: “They were strange things because they had a little motor and you could hear them go ‘chung chung chung chung, chung, chung’. And then they’d stop and you didn’t hear anything and then there was a bang when they hit the deck. You’d listen and they were a bit nerve-racking. You thought, where’ve they gone? Then there’d be ‘thing bang’, but the thing was, we used to all say, if you heard the bang you knew you were still alive.”

The Royal Observer Corps had to plot the course of the doodlebugs, so the pilots could be told where to intercept them. In 1944, according to the West Sussex County Times, some 23 fly bombs fell in the Horsham area in three months during the height of the bombing: “The first of the robots to land in the district came down at Marlands, Itchingfield, on June 6, causing damage to the stables and houses on the estate and killing about 50 chickens.”

Christ’s Hospital was damaged and a woman was slightly hurt after a flying bomb exploded in mid-air when it was shot at. The last one in the area was recorded at Rudgwick on August 13, 1944, while on July 21, 1944, a field of wheat at Chesworth Farm suffered considerable damage.

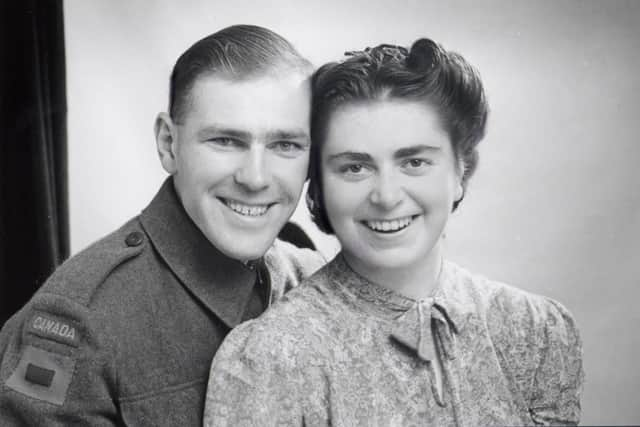

Romance and Marriage

Ethel Exler said: “I met my husband in the war. He was on a searchlight and gun turret in a field at the bottom of our garden. He used to peep at me through the allotments when he was supposed to be looking for enemy aircraft. When I was married in 1943, everybody sort of came together and some gave a bit of that and some a bit of this and we managed. I borrowed my wedding dress. It was secondhand. A very close friend of mine was about my size, and she got it. I don’t know how she got it. You had to give up coupons so if you bought a wedding dress you might go without shoes. My sister had it after that. So that wedding dress did three weddings.”

Entertainment

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHorsham had five cinemas to choose from, the Ritz (now the Capitol), the Odeon, the Capitol, the Carfax and the Central. The radio was run by an accumulator, a large heavy battery that had to be recharged when run down, often at Quicks in East Street.

Alan McMillan said: “The funny thing was with the old radios, half the time we couldn’t understand what was on it, you know. It was so crackly and that sort of thing.”

Jack Scrase, quoted by Cliff White, said: “Dances continued at the Drill Hall, at the Nelson Arms and at the Black Horse, both formal and informal affairs going on throughout the war. Many of the young ladies of the town also went along to the Searchlight Dances held at the camp at Broadbridge Heath.”

In It Together?

John Buchanan, junior reporter for the West Sussex County Times, talking to Cliff White about the Land Army, wrote: “The class divisions in the town were very sharp in those days; the golf club had a County Section, a Town Section and Artisans who couldn’t use the Club House. Very often the Artisan members were the best golfers! It was in the town itself that the divisions were very sharp, between the professions and between the trades people and between them and the shop workers and the farmers who came in, and didn’t they protect those divisions closely.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Christian, from Brookfield Farm, said: “We had Land Girls in about 1941. I think their role was to entertain the farmers’ sons! In the main the girls did very well. The Horsham Home Guard marched out one day with a Smith’s gun. It had made up wheels, a barrel and when you met the enemy, you turned it on its side and fired. It fired a 7lb jam tin full of nails! That’s how well prepared we were.”

There were armed hold-ups at the Ritz Cinema and the Lorna Doone Café, Southwater, where the man demanding £5 was fought off by the female owner.

Mrs Shirley Glaysher, on food, said: “Sunday a joint, Monday cold meat, Tuesday 6d of scrag end for a stew, Wednesday either mince, sausages or rissoles, Thursday liver or steak, Friday was fish, Saturday corned beef, sausages or fish and chips from Pizers in Elm Grove.”

Ken Parfitt said: “Living in the country, of course, with the rationing, you always knew somebody that caught rabbits. Rabbit was a staple diet and after a while you boiled it, you stewed it, you roasted it, you made it into broth, you did everything you could think of to try and decide to get rid of the fact that it was rabbit.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Buchanan tells a story of councillor Nellie Laughton, who liked to help the police: “A convoy of Canadian tanks was coming through the town. A dozen maybe. Somehow three got into Middle Street. The Canadian’s own military police saw there was a problem with the narrowness of Middle Street and diverted the rest around the Carfax. This was Nellie’s big moment. Nellie went down Middle Street ordering the three tanks back. She waved her arms and shouted, all black hat, scarf and handbag, a sort of over-sized bat. The man in the first tank’s turret made the mistake of turning the turret round. The gun was not all that big but it went through a draper’s plate glass window. The man in the turret reversed it and the gun went through a chemist’s shop window on the other side. After that, all the tank turrets swung, as the soldiers followed Nellie’s instructions. There seemed to be glass, curtains and underwear all over Middle Street and draped on the guns. Did we report it? No, censorship.”

A message from the Editor, Gary Shipton:

In order for us to continue to provide high quality and trusted local news, I am asking you to please purchase a copy of our newspapers.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our local valued advertisers - and consequently the advertising that we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you helping us to provide you with news and information by buying a copy of our newspapers.

Our journalists are highly trained and our content is independently regulated by IPSO to some of the most rigorous standards in the world. But being your eyes and ears comes at a price. So we need your support more than ever to buy our newspapers during this crisis.

Stay safe, and best wishes.